- Specifically, these retailers act as though expected sales revenue will increase as the number of outbound promotional customer emails increases, without any boundary or penalty for over-contacting their customers.

- These retailers also treat customers as largely fungible; in short, every customer gets the same contact policy, measured by the number of direct emails they are eligible to receive each week. I didn’t get the impression that these retailers actually believe that customers are fungible, only that in practice, there is no differentiation across customers given their historical behavior or any measurable performance data.

- Finally, there are broadly-held and deeply-rooted perceptions amongst these retailers’ brand and product managers that any change in business as usual will dilute sales revenue and can’t be tolerated.

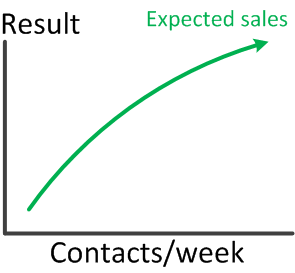

Here is the way we’ve seen sales revenue dynamics actually work when augmented by measurable evidence from customer behavior. The first expectation (which is not usually supported by actual performance) is that sales revenue will increase as you continue to increase the number of contacts per customer per week. Some retailers place an upper bound on the number of contacts per customer per week, and others also place a floor on the minimum number of contacts for some classes of high-value customers. Nonetheless, the widely-held practice is that since the variable cost of an email is virtually zero, you may as well send as many emails as you can, to maximize total contacts and to reduce the average fixed costs of email communications.

Expected sales given varying number of contacts per week

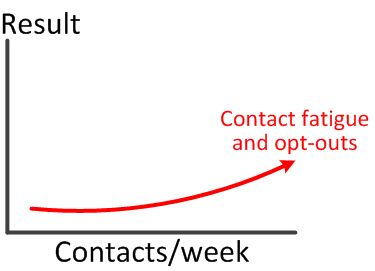

Working with one of the country’s largest apparel retailers, we found that there are very real costs to over-contacting customers. Short-run revenue losses can result from contact fatigue, by reducing the customer’s interest in opening or clicking through the email to a landing or promotional page. Long-run revenue losses can result from opt-out activity. Some enterprising retailers have introduced “opt-down”, which actively asks the customer to receive at least one email per week, but not to leave the retailer entirely. (Why don’t they ask this of every customer?)

Unexpected costs for contacts per week, reflecting contact fatigue and opt-outs

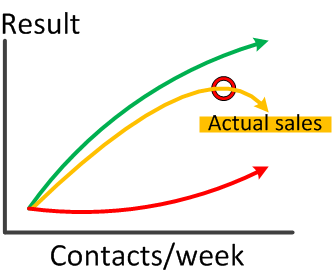

When you subtract revenue losses from expected sales revenues, you can determine the net sales revenue per contact per customer: for the average customer. There’s an important contrast in the accelerated lift in expected sales for small number of contacts, while it often takes a larger number of contacts in order to drive fatigue and opt-out. Hence there’s a sweet spot for the average customer.

Expected sales revenue minus unexpected costs yields the actual sales for the average customer

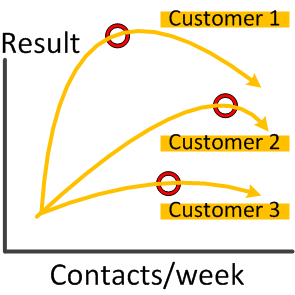

But hold the phone. Is every customer the “average” customer? Our findings provide strong evidence there’s no such thing. Some customers love the brand and love the shopping experience. Others are happy to be reminded of their brand affinity, even if they aren’t going to shop every time they’re contacted. Many customers are indifferent and route most of these emails to the trash heap. Yet others rarely shop, buy small-ticket items, aren’t promotionally-driven, and shop out of convenience. What we’ve seen is that behavioral segments of customers respond very differently, and hence exhibit different sweet spots in terms of contact strategy.

Each customer has a unique sweet spot for contacts per week

What we’ve also found consistently amongst our clients who want to optimize their contact strategy is that a) most haven’t set up the proper tests to explicitly measure for contact fatigue or opt-out rates, b) most don’t know how to balance the competing goals of driving sales and margin, maintaining customer repeat purchasing, and meeting brand and partner marketing volume goals, and c) can’t break well-worn organizational patterns of staying the course and sending as many emails as you can; because after all, email is “free”!

The good news is, measuring and scoring customers for contact fatigue and opt-out is easier than you think; robust solutions for maximizing sales margins while also meeting customer contact strategy and brand exposure goals exist and work really well; and case studies exist that prove this is not a zero sum game where someone needs to lose in order for someone else to win. However, there are costs to keeping a level playing field that mimics the past promotion and circulation policies, and most organizations would be better off actually knowing the magnitude of these economic trade-offs rather than pretending they’re either too hard to measure or too soft to be practical.